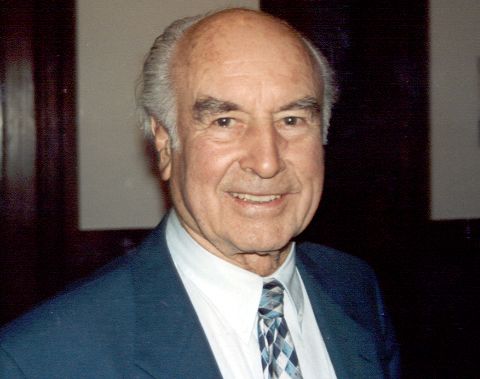

On 16 November 1938, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann was researching drugs to help women in childbirth when he synthesised lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25).

At Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Hofmann isolated compounds of the ergot fungus and combined them with other molecules in the hope of creating a respiratory and circulatory stimulant that could induce childbirth and stop post-partum bleeding.

On his twenty-fifth attempt he combined lysergic acid, a chemical derived from ergotamine, with diethylamine, a derivative of ammonia. During testing the animals became restless, but the substance aroused no pharmacological interest. The drug was shelved.

But the molecule continued to captivate Hofmann.

“I could not forget the relatively uninteresting LSD-25,” he explains in his book, LSD: My Problem Child.

At the height of World War II, Hofmann had a “peculiar presentiment” to resynthesise LSD-25. During this process, he accidentally absorbed the drug through his skin and became intoxicated.

Three days later, on 19 April 1943, Hofmann ingested 250 micrograms of LSD-25 diluted in water — “the smallest quantity that could be expected to produce some effect” — to see for himself if the substance had caused the dreamlike state.

What happened next? The first full-blown acid trip.

“By now it was already clear to me that LSD had been the cause of the remarkable experience of the previous Friday, for the altered perceptions were of the same type as before, only much more intense. I had to struggle to speak intelligibly. I asked my laboratory assistant, who was informed of the self-experiment, to escort me home. We went by bicycle, no automobile being available because of wartime restrictions on their use.”

The inaugural acid trip and its famous bicycle ride are celebrated by the psychedelic community as Bicycle Day on 19 April each year.

But Hofmann was not in a festive mood. As the trip intensified, he experienced visual distortions, paralysis, terror and demonic possession. Inebriation came in waves. The afternoon was punctuated with moments of lucidity before the room began to spin and the furniture became animated with malicious intent.

“I was seized by the dreadful fear of going insane. I was taken to another world, another place, another time. My body seemed to be without sensation, lifeless, strange. Was I dying?”

After a doctor’s examination noted no abnormal symptoms except for extremely dilated pupils, Hofmann’s horror receded and gave way to gratitude as his mind capsized into a synaesthetic reverie.

“Now, little by little I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colours and plays of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes. Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images surged in on me, alternating, variegated, opening and then closing themselves in circles and spirals, exploding in coloured fountains, rearranging and hybridising themselves in constant flux.”

In the afterglow the next morning, Hofmann noted a sense of profound wellbeing and renewal: “The world was as if newly created.”

But the world and its psychedelic compounds had existed for millennia.

Hofmann had simply given birth to the latest manifestation.

This blog is the first chapter of a series titled 'What is the psychedelic renaissance?'

Subscribe to my newsletter Afterglow to take the trip.